|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|---|

|

|

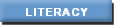

Developing a Visual Idiom through Kamishibai Gaitő kamishibai-ya, or the early street performing artists in Japan, drew upon interactive storytelling techniques extensively to capture and hold the attention of their young audiences. Having the audience tell the story along with the performer or contribute key elements of the story as it unfolded functioned to keep children actively engaged in performances and intrigued enough to come back for more stories day after day against a distracting backdrop of busy urban streets. Teachers in large classrooms might want to draw upon these techniques for some of the same reasons and with an additional motive that has practically become a truism of 21st century education: children learn more when they are actively involved in their learning. (For a discussion of these and other techniques of interactive telling, see chapter 4 of my book, The Kamishibai Classroom: Engaging Multiple Literacies through the Art of "Paper Theater" [Libraries Unlimited, 2010]. To see a video of a recent performance of several original story cards that appear in the book, click here, and here, and, for an interactive song in Japanese, click here).

Although it is fun to develop stories that will engage the audience in the telling, whenever feasible I like to have all the students in a given classroom or workshop each create their own original stories because this engages them most deeply in all aspects of the format and affords them an invaluable opportunity to develop their own visual idiom or style of visual communication. It also gives me a chance to see the diverse range of unique visual styles of which a group of students is capable when they are allowed to draw upon the whole range of modes and topics of interest available to them. When instructing children in kamishibai techniques, I never tell them how or what to draw, but I do give them suggestions about different perspectives and camera angles they might try. American students typically draw from middle to far distance-tiny characters with lots of minute details-so it can be a challenge at first for them to zoom in closely on an important part of their drawings. Rather than drawing something for them or having them copy from photos or the work of other artists, I generally will suggest in light pencil, the size and position of the object on the card and its scale in relation to other objects in the scene. While students may certainly take inspiration from other sources, especially if they are exploring an unfamiliar topic, the drawings they come up with must be translated into their own idiom (i.e., not copied) because kamishibai requires that they not only repeat those images over many cards, but also change the angle and perspective. This requires taking an image in ones mind and playing with it; manipulating it in mental space and asking, "What would this look like from the back or when viewed from above, or if it were moving?" These challenging decisions over several cards, synchronized with the oral telling of a story that is centered on the child's own concerns and purposes, develop over time his or her confidence in an emerging style or idiom of visual communication that is very much his or her own, and the variety and uniqueness of expression can be seen across any group of children's performances. I recently had an opportunity to rediscover this wealth of styles and approaches when conducting my dissertation research in a wonderful 3rd grade public school classroom setting of 22 students in New Jersey. Although the location and students' identities will remain anonymous, I would like to thank all the parents who generously granted me permission to use their children's performances for this article. In what follows, I will outline some of the sources of inspiration for these stories, but I think the uniqueness of the images speaks for itself through performance (click on the accompanying links to see videos of the performances). The Personal Story As one would imagine, personal experience provides a practically inexhaustible source for unique storytelling opportunities, as these first two performers demonstrate. Drawing upon their knowledge of the vicissitudes of pet ownership, they take two very distinctive perspectives on the same familiar little creature, the hamster. In the first story, entitled "Rover and Huey," the artist explores the clever trickery to which a dog might resort, if he also wants to take part in the enjoyment of the cuddly hamster (for a video of the performance, click here).

In the second example, entitled "Too Much Food!," the author of the story finds a humorous lesson in the extremes of over-zealous pet care! (Click here to hear the story).

In both cases, the students informed me that these stories were based on actual experiences, although they certainly translated them into their own idiom and may have exaggerated them here and there for effect! As can be seen from the background, these young performers took part in the outdoor, community festival performance with me above, as well as in classroom performances with their peers, teachers, and parents. Community festivals are a wonderful way to give young performers opportunities to try out their stories on new audiences and also to get closer to the roots of kamishibai as a street performance art. Folktale Variants Another source of inspiration that teachers routinely draw upon in having students create stories is the folktale, and the next two performers chose this genre without any prompting from their instructor. Each developed her own unique take on a familiar tale and translated it into her own visual idiom. In the first instance, "The Were-wolf and Jack," readers familiar with kamishibai may recognize a variant of the kamishibai version of "The Three Magic Charms" (Illustrated by Eigorő Futamata), only in this instance the "mountain witch" (yamanba) has been translated into a were-wolf girl and Jack, the eponymous hero, lives with his father instead the old priest. Though the inspiration clearly comes from Futamata's illustrations, the student has put her own spin on them and recreated from memory what were to her the most valuable aspects (to see the video, click here).

As can be seen from the background, these performances took place in the classroom for parents and peers. The next student also chose to create a variant of a folktale, this time the Panamanian tale "El Conejito," which she changed into "Big P Gets in Danger" (to see video, click here).

Instead of a rabbit as the main character, this author chose to set the story in China with a giant panda, named Big P, who meets along the way a fox, a tiger, and a bear, instead of a tiger, fox, and lion. As with all great storytelling, these familiar tales are translated into a new environment, as well as and a new idiom, and both tellers have recognized what a great medium kamishibai is for visually depicting the perennial chase-scene! Popular Culture and the Media Of course, another rich source of inspiration for students of all ages-especially, it would seem, for boys-is the action-packed media of television, films, and videogames. As I describe in the first chapter of my book, the history of kamishibai grew out of a national fascination in Japan with silent film, and, although it is often forgotten today when so many folktales are recreated in kamishibai form, the original stories were much more commonly based on the lurid underworld adventures of gangsters, spies, and superheroes. Our next performer drew upon his knowledge of the workings of the CIA and the gangster underworld to bring a pair of miscreants to justice (upside down!) in "Slammer Day for Bob and Randy." (To see the video, click here).

By bringing kamishibai closer to its street-performance roots, this young author also reminds us that kamishibai is not limited to the fantasy or folktale genre, and in fact any genre that can be made into a film-a nonfiction documentary, for example-can be adapted to the kamishibai format. The Natural World and Concerns for Our Environment In this same vein, an ever-increasing concern for children today is the environment and how to protect it. Here we have two performers with very different takes on human interaction with the environment. The first one, entitled "No Polluting," explores how humans can work together with the increasingly anxious animal populations to help keep their environment clean (to see this video, which is in two parts, click here and, click here for the continuation).

And, in our final example, "Save the Catfish," the author shows how animals of differing species can work together to protect themselves from bumbling but predatory humans. This student illustrated the climactic moment of his story several times until he zoomed in to just the right effect! (To see video, click here).

In Conclusion Although this represents but a small sampling of the wealth of ideas and styles of communication that emerged within this class of 22 students, these stories open a window onto the complex thoughts and preoccupations of third graders as they grapple with communicating their understanding of real world problems and everyday concerns. As I work with students, I am perpetually amazed and delighted by what they come up with and am constantly reminded that, though we may all have suggestions to improve a performance or visual image (and in peer-critiquing sessions, these students had a lot to suggest to improve the performances of one another!) the vision and ideas are uniquely the creation of these students and not something that I or any other instructor could successfully attempt to reproduce or embellish upon. This is what I mean when I speak of the development of a visual idiom, and as any professional illustrator would probably agree, developing a unique visual idiom is an ongoing and fascinating lifelong pursuit! I have heard some teachers express concern about involving all children in such an extensive drawing project because of those students in the class who may not self-identify as "artists," but I would invite them to consider the integrated role visual images play in a kamishibai story. With kamishibai, the cards are not meant to be viewed individually as masterpieces displayed on the wall in a gallery, but rather for how effectively they communicate in synchrony with the other modes involved: the telling and the manipulation of the cards. As I mention in my book, I have often heard people in kamishibai circles in Japan say that a good storyteller can bring even the simplest images to life, while an ineffective storyteller can render even the most accomplished illustrations dull or lifeless (see The Kamishibai Classroom, p. 9). While we may not all choose to pursue a career in the visual arts or design, there is much to be said for all students having opportunities to develop confidence in their own visual idiom, just as they are required to do with writing in the current standards and expectations of the classroom. Most significantly, they will learn through this process how visual images communicate meaning in a world where increasingly images are taking over the role once reserved for words. Tara McGowan holds a Ph/D degree from the Language and Literacy Division of the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania. She also is a visual artist and storyteller. To find out more about her programs, check her website at http://www.taramcgowan.com.) |

|---|

|

|---|

|

Kamishibai for Kids ~ 2358 University Avenue #179, San Diego, CA 92104 |