|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|---|

|

We are pleased to post this article by Araki Fumiko, our friend, colleague and a leader in the Japanese kamishibai movement. In addition to performing and teaching throughout Japan and the world, she is also a puppeteer and has published many kamishibai stories. "Bunchan," as she is popularly known, will also be spearheading the online World Kamishibai Forum series of workshops, beginning in the fall of 2020, which will introduce the variety of performance styles, applications, and venues for kamishibai developing in Japan and around the world today. Stay tuned for more details about the series as the organizers, Tara McGowan, Walter Ritter and Donna Tamaki, post more information about the event in the near future. Click here to see Bunchan's recommendations from the Kamishibai for Kids catalog! This article was first published in Japanese in the journal "Kamishibai bunka netto waaku (Kamishibai cultural network)", nos. 67 and 68. This translation is by Donna Tamaki and Tara McGowan. Photographs, courtesy of Donna Tamaki and Katsunori Michiyama. A Widening Path: Bunchan Shares Stories of her Travels with Kamishibai

Introduction I was invited to attend a kamishibai festival in the two Mexican cities of Monterrey and Durango from November 14-25, 2019 and experienced firsthand how popular kamishibai has become in the country. How many years ago was it that Margaret Eisenstadt of Kamishibai for Kids came to Japan and met with my mentor Ute Kazuko and me? I can't help but feel that my path to this festival in Mexico was set those many years ago, and the path has grown wider and wider. Monterrey: My Colleagues and Getting Adjusted The events from the 14th to the 20th took place in Monterrey, the third largest city in Mexico. I performed together with Lorenzo from Vera Cruz (Mexico), Lenin from Peru, Miguel from Columbia, Deyanira from Mexico City, Donna from the US, and Roberto, Dora and Grace from Monterrey. Etery served as my interpreter during my entire stay and Etery's mother, Teresa Farfan Garcia, was my host and the organizer of the events in Monterrey. They were all very easy to get along with so I felt at home right away. Everyone called me by my nickname "Bunchan."

The opening event was held at a theater on the 15th. Some participants narrated stories; others performed with kamishibai or puppets. I was last on the program and performed two kamishibai stories, I thought it was a rope but... and Manmaru, the Ninja, with my ninja finger puppet playing an important role in the performance. Although I had been worried about language and cultural differences, I was relieved when I saw the enthusiasm of the young audience. It gave me the confidence to do my job. Fascinating Experiences and Audiences During the next five days I performed kamishibai in the most unexpected places. It was a demanding schedule but I had some fascinating experiences. On one day I performed at an immigration office where South Americans hoping to emigrate to the United States were staying temporarily. People were pouring out into the street, but all of the children and adults enjoyed our performances. Lenin, one of my fellow performers told tales using a large, cloth storybook that he sewed beautifully by hand. On another day I performed kamishibai at a rather shabby-looking center where 40-50 children with food insecurity came for various activities. With the help of Etery, I performed Momotaro, the Peach Boy, in addition to my two usual stories.

Later that day, I attended an event memorializing Celso Piña, a world-famous Mexican musician and accordion player, who had died earlier that year. We performed on a street in the working class neighborhood where he had lived. After we finished, we visited Piña's home which is now a museum. A lot of people appeared out of curiosity when they heard that someone from Japan was at the museum! Workshops

On the third day, Donna gave a workshop at the home library of Grace, one of the volunteers and interpreters. Donna spoke about the work of Margaret (Eisenstadt) and the founding of Kamishibai for Kids. Old photographs of my mentor, Ute Kazuko sensei, and myself appeared, and I remembered fondly our visit to New York long ago. Here is a picture of Margaret, me, Ute-sensei, and Donna in Tokyo in the 1990s! My workshop was on the next day, and I told the group about my kamishibai activities in Japan. Using my two usual stories and Why Crocodiles Don't Eat Chickens as examples, showed the participants how to pull out the cards, alter their voices, move the cards, etc. They all tried using the techniques themselves and did a terrific job. Everyone had a great time. During the question period, Lorenzo asked what I thought of the kamishibai he had made, saying he had been nervous performing it in front of a kamishibai performer from Japan. I was expecting someone to ask this question and said that I was surprised when I first saw it but that I enjoyed it. I said that there are no absolute rules about kamishibai. I just wanted them to know what the Japanese kamishibai traditions are like but that they should keep experimenting and creating their own works. Even in Japan, kamishibai did not start out in its present form and has gone through many transformations. I believe it is good to have people creating new forms of kamishibai. School in the Sierra Madre Mountains On my fifth day in Monterrey, a jeep - without a back and front windshield - came to pick us up and took us to a school in the mountains. The roads were three times steeper and more winding than the infamous Iroha-zaka in Nikko - and very narrow. As the jeep drove up the road at top speed, Etery laughed watching me grab onto the front seat. I thought, "How could there be a school in such a place?" But eventually, houses and the school, where the students had been eagerly awaiting us, appeared. They watched each performance with great enthusiasm. That night we stayed at a cabin nearby and returned to Monterrey the next day.

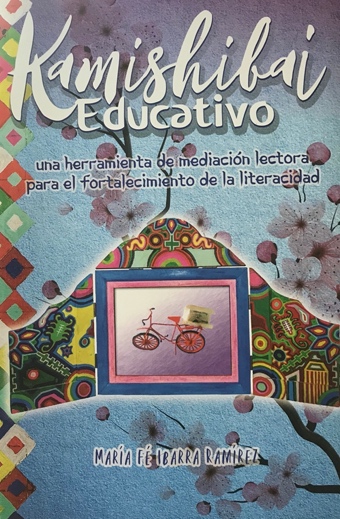

On the 19th of November, 2019, I had already been in Mexico for six days. We returned from the mountains to Monterrey, and performed in a library. In addition to my usual two stories, I added Why crocodiles won't eat chickens and everyone loved it! There were loads of questions afterwards: "Are Japanese watermelons square?" "What kind of house do you live in?" "What is good to eat in Japan?" Three Hundred Km. to Durango on the Night Bus Later, we took the grueling nine-hour, overnight bus ride to Durango. When we arrived, we were met by storytellers from Puerto Rico, Chile, and Venezuela, as well as Tara McGowan from America and Yumi Michiyama and her husband from the International Kamishibai Association of Japan (IKAJA). The organizer of the Durango Festival was Maria Fe Ibarra Ramirez.  Durango is more rural than Monterrey. It is a beautiful town with really clear blue skies. Under that blue sky, the following day after breakfast, we headed to the hall where the Durango festival was to begin. Or rather I should say that I was in a state of suspense, not knowing what was going to happen next. The truth is that I hadn't seen a schedule in the whole time I was in Mexico, and every day we would only find out in the morning what we were expected to do and where we were going. The Michiyamas and I joked, "There doesn't seem to be a word for "programming" in Mexico. We will just have to relax and be patient." We didn't find out until we were at the rehearsal in the auditorium that after the opening ceremonies, Yumi Michiyama would present first and I would be second. The auditorium was so large, it could hold 400 people. In my heart, I was exclaiming "No way!!" followed by "There's no turning back now!"  The Two Guests from Japan Open the Festival And so, the festival began! The auditorium was almost full with elementary and middle school teachers and parents with their children. There were many words of congratulations from different people on the stage. After that, Yumi Michiyama from IKAJA took the stage and explained about how the International Kamishibai Association of Japan got started, how to pull the cards out of the stage, how to perform, and about peace and kamishibai. She performed Grow, Grow, Grow Bigger, The Duck King, Never Again and Everyone Clap. After presenting a stage and kamishibai sets to the hosts, she got a big round of applause. The Appeal of Kamishibai and How to Make Performance Fun After a short intermission, it was finally my turn to present. I had decided that it was best if I just did what I always do, so I calmly stood before 400 people and began. My topic was "The Appeal of Kamishibai and How to Have Fun Performing." I had been given 90 minutes so I had time to do a variety of things, but these are the highlights: First, I explained that in Japan there are many kamishibai performers, who perform in a wide variety of styles. There are many kamishibai groups large and small, including IKAJA, and each has their own approach to their activities. I went on to say that the kamishibai stage is called the world's smallest theater and therefore, it is a form of drama. I showed them how to use finger games and hyoshigi (wooden clappers) to capture the attention of the audience. I demonstrated how lights could be used to improve visibility of the images from a distance and about when to use paper curtains.  After we did some finger games, I performed I thought it was a rope, but... and explained about the most effective way to pull the cards out of the stage in order to expand the viewers' imaginations. Then I said, "Won't someone from the audience try it?" and a female teacher volunteered. Her performance was very different from mine but was interesting in its own right.  Through this exercise, I was able to demonstrate that kamishibai is brought to life through performance, and with every performer it is different. After that, I performed Manmaru, the Ninja. Through the interactive clapping of the audience throughout the story, everyone in the auditorium could participate and feel as one. The African folktale Why crocodiles don't eat chickens can only be fully appreciated and understood when the voice of each of the characters in the illustrations is distinct. This gave me the opportunity to demonstrate how to create and project voices for different characters. This is an important exercise if you want the images to become animated. There was a great swell of laughter when, in the course of the story, I said the crocodile's punchline: "I was just about to eat my little sister!" Finally, Etery gave a summary, instead of a line by line translation of the story, before I performed the folktale The Tongue Cut Sparrow. This was rewarded with enthusiastic applause. Finally, Etery gave a summary, instead of a line by line translation of the story, before I performed the folktale The Tongue Cut Sparrow. This was rewarded with enthusiastic applause. A Gift from the Audience Just as I was making my final bow and thanking the audience, a boy of about seven dressed in a suit and bowtie walked up on stage. He spontaneously came up to shake my hand and then, without saying a word, went back to his seat. A warm applause followed from the audience. After I had answered several questions from the audience, the same boy came up on the stage again and this time, again without saying a word, shyly offered me a piece of gum. This is a happy memory that I treasure. Of course, someone asked the obvious question: "We have just seen two entirely different performance styles. Which one are we supposed to follow?" I answered: "I'm sorry if you feel confused, but the fact is that there are no hard and fast rules with kamishibai. You will have to decide which style you like better and follow that one. "Well, in that case, I will choose yours!" came the answer. The performers taking part in the festival from Mexico, Columbia, Peru, Venezuela, the US and elsewhere all had fun freely performing kamishibai, and there were many hand-made stages with colorful designs. With some, the doors opened with one image and closed with another. Some stages were designed so the cards could be pulled from the left, some from the right, and some from the top. And when it came to performance, I often thought, "Wow, you can do this with kamishibai!" I learned a lot from their inventive approaches. As kamishibai goes out into other countries and comes in contact with people from other cultures, it will continue to grow as an art form. I am looking forward to seeing this happen. It made me think that I too need to hone my craft and continue to develop my own methods of performance. My Final Day: Tara's History of Kamishibai The next day of the festival was a conference in a different auditorium. I learned a lot from the presentation of the US participant Tara McGowan. It provided the background for how kamishibai developed out of magic lantern shows and Edo-period utsushi-e. I really hope Japanese audiences will also have an opportunity to hear it.  Uses of Kamishibai in Mexican Classrooms After that, there was a series of presentations on how kamishibai is being used in schools in Mexico. There are an increasing number of classrooms where kamishibai is being used in instruction. Marie Fe's recently published book about kamishibai (see below) is doing a great deal to enhance the spread. In Mexico, children create their own stories and illustrations, they make their own stages, and they perform for friends and family. Kamishibai helps them to develop their own thinking and improve their reading, writing, and drawing. The children performing kamishibai in Mexico were full of enthusiasm and energy. In this sense, the Japanese have much to learn!   Why the colorful stages? I had seen so many colorful stages at the festival, and I couldn't help thinking, "They are beautiful, but won't the illustrations inside the stage lose their impact?" When the Q and A started, I raised my hand and asked, "In Japan, I have rarely seen stages that are not brown or black. Why do you paint your stages with so many bright colors?" The answer was: "That is the cultural difference between Japan and Mexico. The colors express our Mexican spirit." I had to agree. Conversely, I was asked: "Why are Japanese stages that particular size," and I had to explain that it was based on paper sizes and publication practices in Japan, but that there were also larger and smaller sized stages." The festival continued on for many days after that, but my time in Mexico had come to an end and I had to return home. I had learned a lot and met many great people. I am grateful to those who gave me this opportunity. Thank you!!

|

|---|

|

|---|

|

Kamishibai for Kids ~ 2358 University Avenue #179, San Diego, CA 92104 |