|

|

KAMISHIBAI - A BRIEF HISTORY

By Tara McGowan

Kamishibai, (kah-mee-she-bye)

or “paper-theater,” is said to have started in Japan in

the late 1920s, but it is part of a long tradition of picture storytelling,

beginning as early as the 9 th or 10 th centuries when priests used

illustrated scrolls combined with narration to convey Buddhist doctrine

to lay audiences. Later, etoki (picture-tellers) adopted these

methods to tell more secular stories. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1867)

and on into the Meiji period (1868-1912), a variety of street performance

styles evolved, using pictures and narration.

The stages used for these early precursors

of kamishibai were  not

as easily transportable as the form that developed in the late 1920s

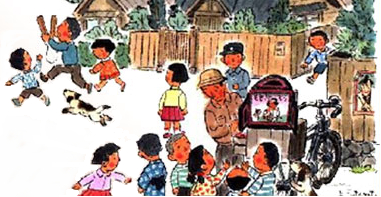

and came to be what we know as kamishibai today. The kamishibai performer

made a living by selling candy, and he could strap the small wooden

stage onto his bicycle with the illustrated cards and his wares and carry

them easily from town to town. Typically, the stories were told in serial

fashion and were so suspenseful that audiences came repeatedly to buy

candy and to hear the next episode of the story. not

as easily transportable as the form that developed in the late 1920s

and came to be what we know as kamishibai today. The kamishibai performer

made a living by selling candy, and he could strap the small wooden

stage onto his bicycle with the illustrated cards and his wares and carry

them easily from town to town. Typically, the stories were told in serial

fashion and were so suspenseful that audiences came repeatedly to buy

candy and to hear the next episode of the story.

Kamishibai is, if anything, poor-man’s

theater, and it flourished during a time when Japan experienced extreme

financial hardship. In the 1930s, Japan suffered from an economic depression

that sent many people onto the streets looking for a way to live from

one day to the next, and kamishibai offered an opportunity for artists

and storytellers to make a meager living. During and after World War

II, kamishibai became an ever more integral part of the society as a

form of entertainment that could be transported easily even into bomb-shelters

and devastated neighborhoods. At this time, it was entertainment as

much for adults as for children.

By the 1950s and the advent of television,

kamishibai had become so popular that television was initially referred

to as denki kamishibai, or “electric kamishibai.”

But as Japan became increasingly affluent, kamishibai became associated

with poverty and backwardness. Eventually kamishibai as a street-performance

art all but disappeared. The artists who had made their living with

kamishibai turned to more lucrative pursuits, notably the creation of

manga (comic books) and later anime, but they never

entirely forgot their roots in kamishibai. In fact, kamishibai is often

seen as a precursor of manga, and its influence can still be

felt in the distinguishing features of these later media.

But kamishibai has never entirely died

out. Kamishibai stories for educational purposes are still being published

and can be found in schools and libraries throughout Japan and more

recently, through the efforts of Kamishibai for Kids, in the

United States and Canada. There are many people, too, who, like Allen

Say, feel nostalgia for the old street-performances, and recreations

of these can be found at various outdoor events and festivals. A particularly

vibrant aspect of the kamishibai revival are the tezukuri kamishibai

(hand-made kamishibai) festivals held at designated points throughout

the year, where people young and old gather to perform kamishibai stories

they have illustrated themselves. There are Japanese kamishibai artists

who have taken their art form to other parts of Asia (Vietnam, Laos,

Cambodia, Thailand), where people are learning to make and perform their

own stories in their own languages. Kamishibai has become a way to bridge

cultural and linguistic barriers. Wherever there are people who want

to gather and share stories, kamishibai will always have a place.

|

|